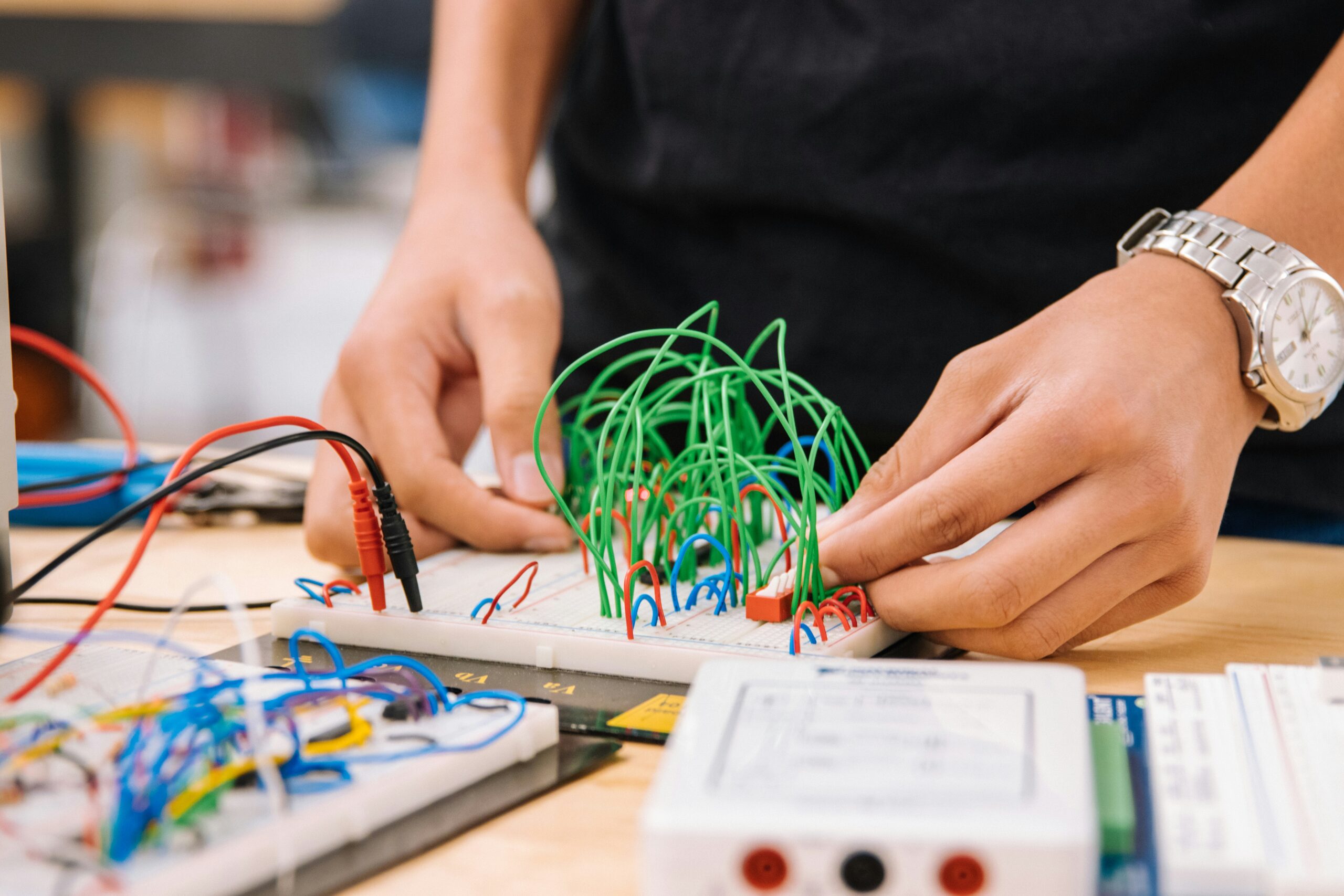

Image credit: Unsplash

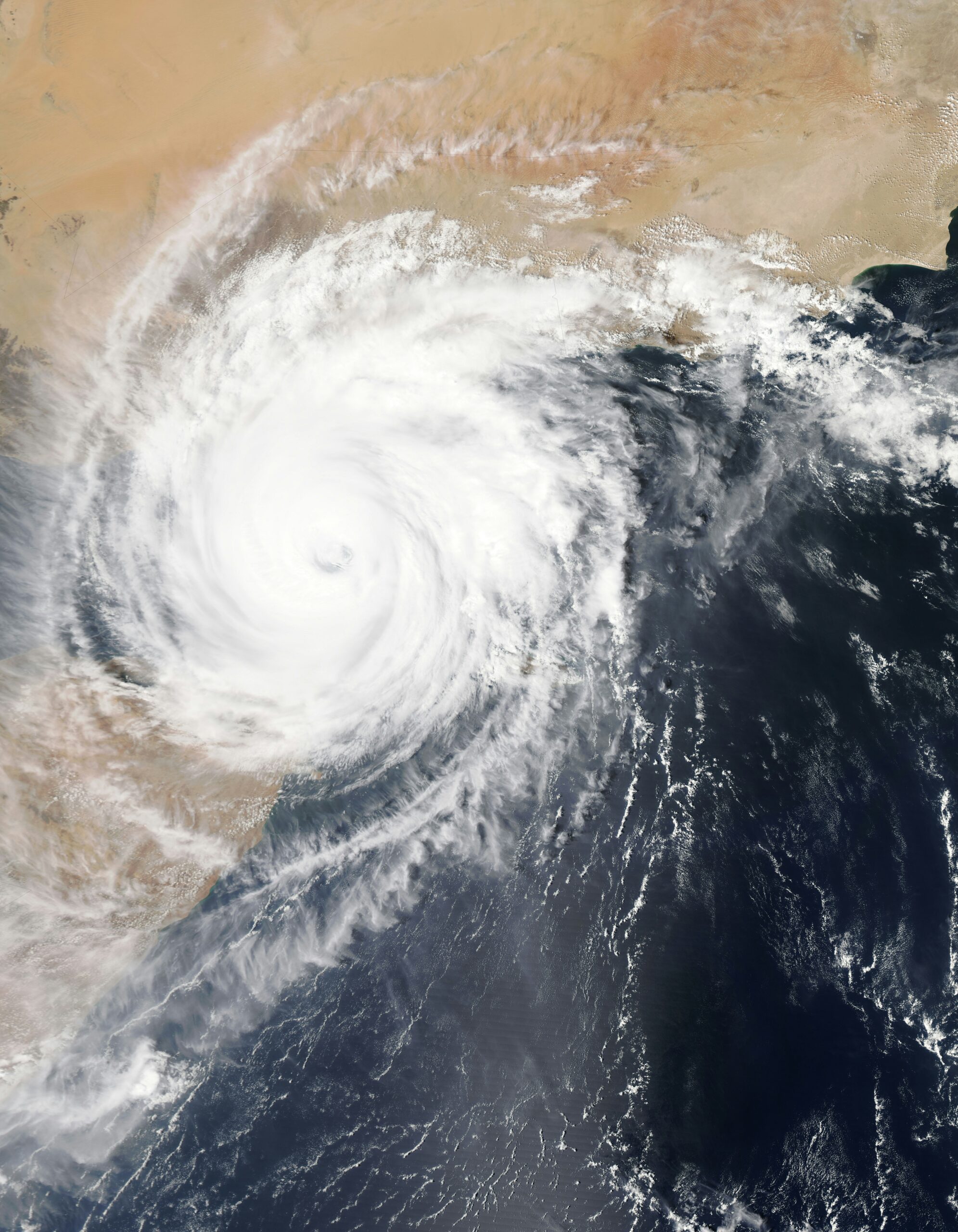

For some, Miami, Florida, has become ground zero for climate change. Overtown is where developers are fleeing rising sea levels and coastal flood risks. This is because Overtown, like districts such as Allapattah, Liberty City, and Little Haiti, sits along the Miami Rock Ridge. On average, it’s only nine feet above sea level, about three feet higher than Miami’s.

As a result of these changes, the development booms in these districts are changing the face of what are historically Black neighborhoods, leading to what some call “climate gentrification.”

Climate gentrification isn’t just happening in Miami, however. It’s occurring in other parts of the US and disproportionately falls on people of color in the process.

What Is Climate Gentrification?

When a neighborhood gentrifies, the incomes, education levels, and rent rise rapidly, says Carl Gershenson, director of the Princetown University Eviction Lab. Because of how these elements correlate, the outcome is generally that, as the white population increases, people of color are forced out due to pricing.

Climate change, however, “molds the way gentrification is going to happen,” according to Gershenson.

It has exacerbated a “pronounced housing affordability crisis” in Miami, where asking rents have increased by 32.3% over the last four years to $2,224 per unit on average – which is higher than the US average of 19.3% growth and the $1,825 per unit, according to Moody’s Analytics. As a result, the typical renter spends about 43% of their income on rent.

While housing demand has soared due partly to Miami’s transition to a finance and technology hub, this has pushed prices up. However, rising sea levels and frequent and intense flooding have made neighborhoods more attractive to wealthy people, as they can relocate from increasing climate hazards, Moody’s says.

“These areas, previously overlooked, are now valued for their higher elevation away from flood-prone zones, which leads to development pressure,” according to Moody’s.

Moody adds that the shift in migration patterns accelerates the displacement of established residents while widening the socioeconomic divide.

According to a 2015 analysis by Florida International University, just 26% of homes are occupied by their owners.

Heartbreaking Costs

Higher property taxes go hand in hand with higher property values. Wealthier homeowners may also demand more city services, which raises prices.

“To see how the elders are being pushed out, single mothers having to resort to living in their cars with their children in order to live within their means … is simply heartbreaking for me,” Nicole Crooks, a community engagement manager at Catalyst Miami, has said.

With climate gentrification occurring in all parts of America and climate disasters exacerbating living costs, Princeton’s Gerhenson has described Miami and Honolulu as “canaries in a coal mine.”

Fredericka Brown, who has lived in the Coconut Grove area of Miami her whole life, stated that her “whole neighborhood is changing” and added that, in her area, “they’re not building single-family [houses] here anymore.” She said that the height of buildings is “going up.”