Image credit: Unsplash

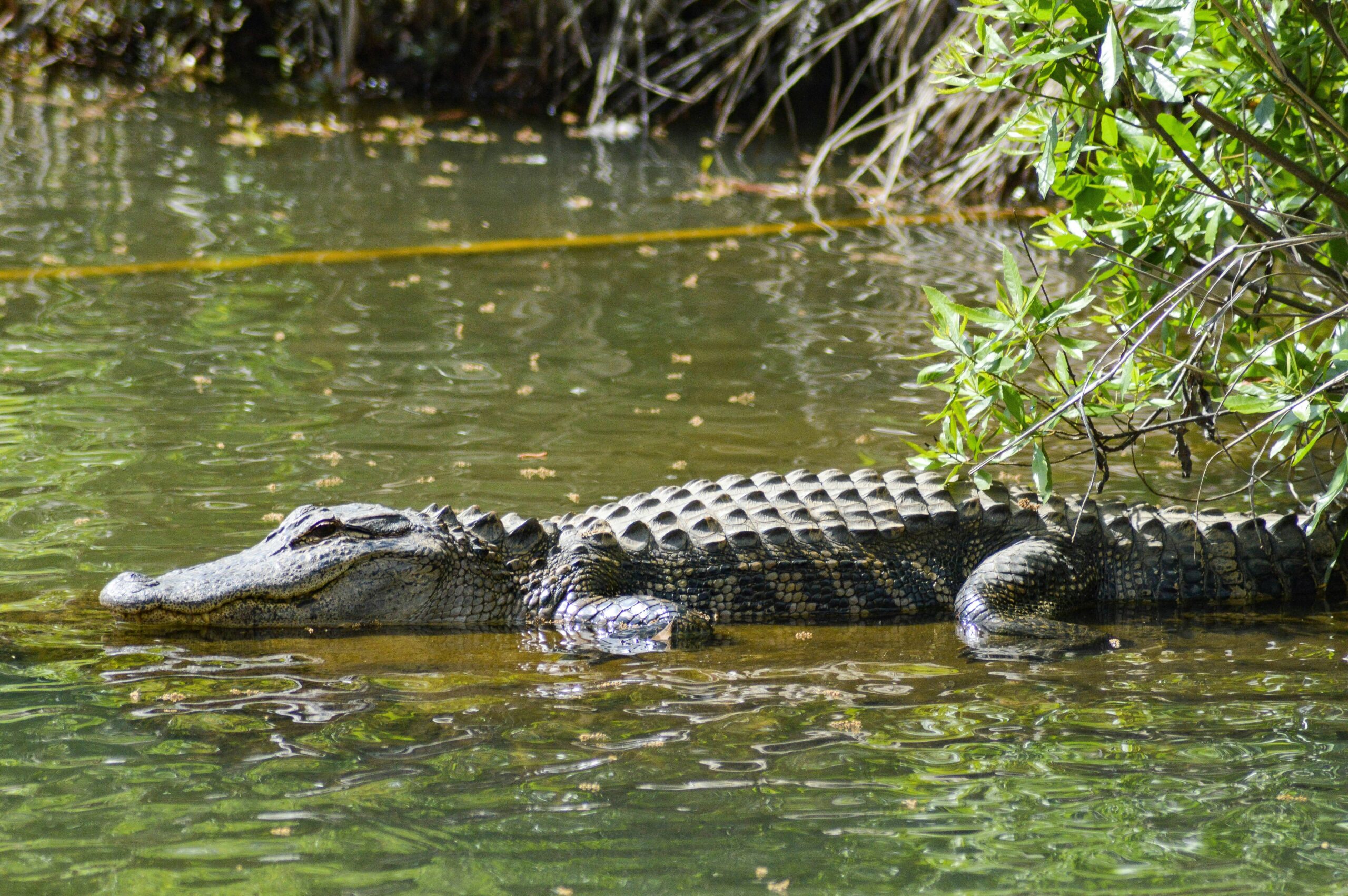

A hypothetical plane crisis simulation exercise involving a scenario where it crashed onto a helipad at the campus shut down streets all around the UMiami medical campus last Sunday morning. Plenty was impacted, including the Metrorail and a bus carrying exercise participants staged as foreign nationals.

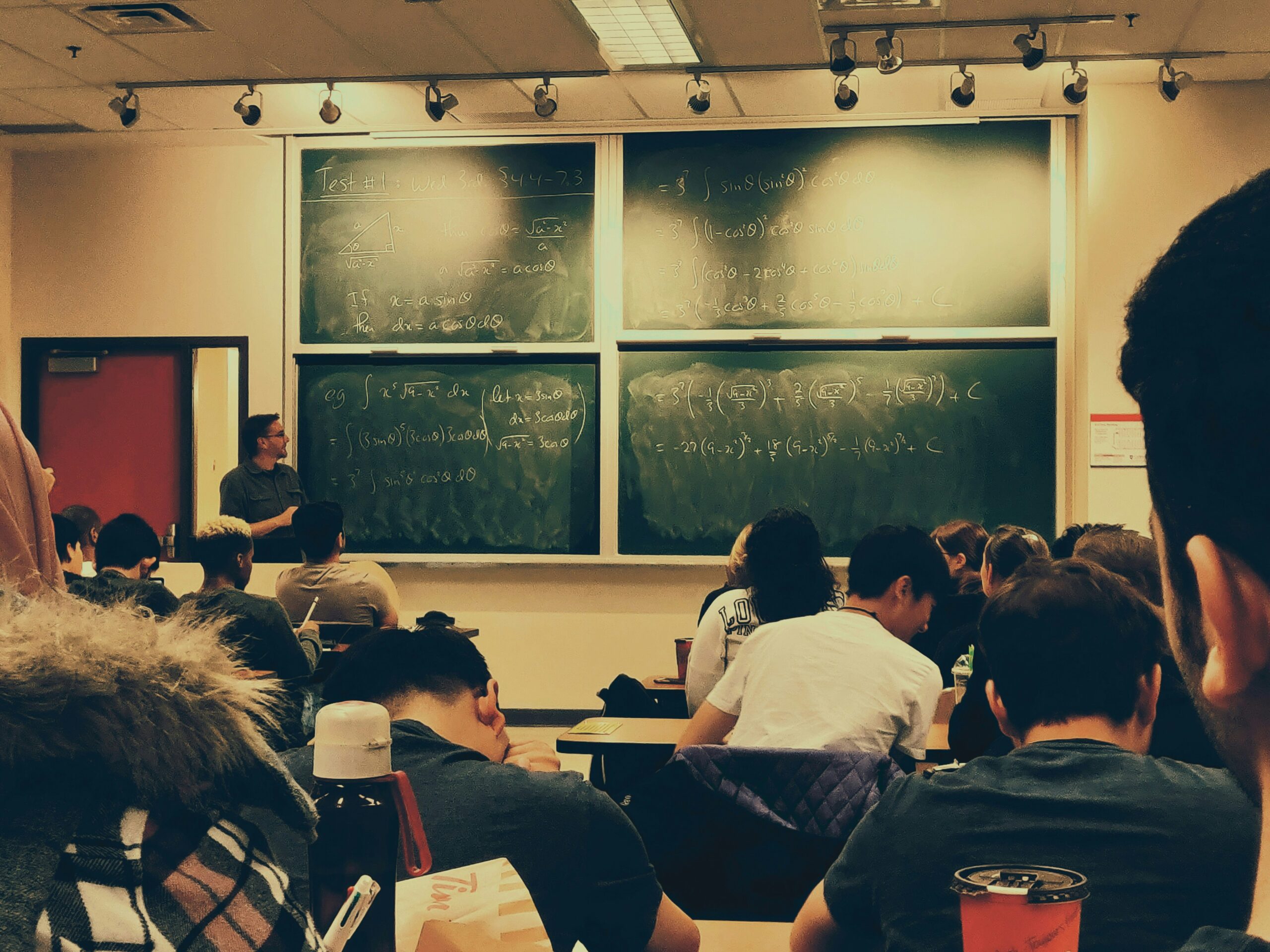

The training exercise involved over a dozen partner agencies, spanning several hours and stretching into the early afternoon. The University of Miami Health System medical campus became the headquarters of the event. After over a year of careful planning, the events went off without a hitch.

According to University of Miami Health System & Miller School of Medicine Emergency Management Director Vincent Torres,

“We are directly in the flight path of Miami International Airport. We do see about 200 flights of air rescue helicopters every year in and out of this campus. So, we identified this as a risk, as a hazard… In accordance with our policy, we want to plan ahead for disasters, and that’s what we’re doing today.”

Torres also noted that the first responders in the crisis simulation weren’t exactly clued in on the details of the day in order to elicit the most natural emergency response possible. That way, their skills could be gauged accurately. Coordinated responses from the City of Miami and Miami-Dade County fire-rescue and police departments were involved, as well as Miami-Dade transit, the American Red Cross, the Consulate General of France in Miami, and the FBI.

Torres stated, “We’ve conducted multiple tabletop exercises with our community partners, with our hospitals, and we’re going to be testing not only first responders in a crash scenario — and you’re going to see technical rescue, you’re going to see triage treatment and transport. You’re also going to see the necessity of transporting and evacuating a hospital.” He continued, “They’re going to actually work through — our operating room staff and our cancer center personnel — are going to work through evacuating the cancer center and relocating patients to our primary acute care hospital. You’re also going to see a surging of patients to our emergency department from the crash scene.”

While access to Jackson Memorial Hospital remained open at all times from NW 10th Avenue, plenty of other avenues were closed in order to accommodate the scope needed for a successful event. The morning and early afternoon saw NW 12th Avenue from NW 12th Street to NW 16th Street, NW 14th Street between NW 13th Court and NW 11th Avenue closed, amongst others.

Torres was focused on the authenticity of the event in order to get tangibly meaningful results. He stated, “We are not a trauma center. But what you will see is, in a real-life mass casualty incident, patients are going to show up where they’re going to show up. They’re going to see a hospital… It’s critically important to make the exercises as real as possible.”

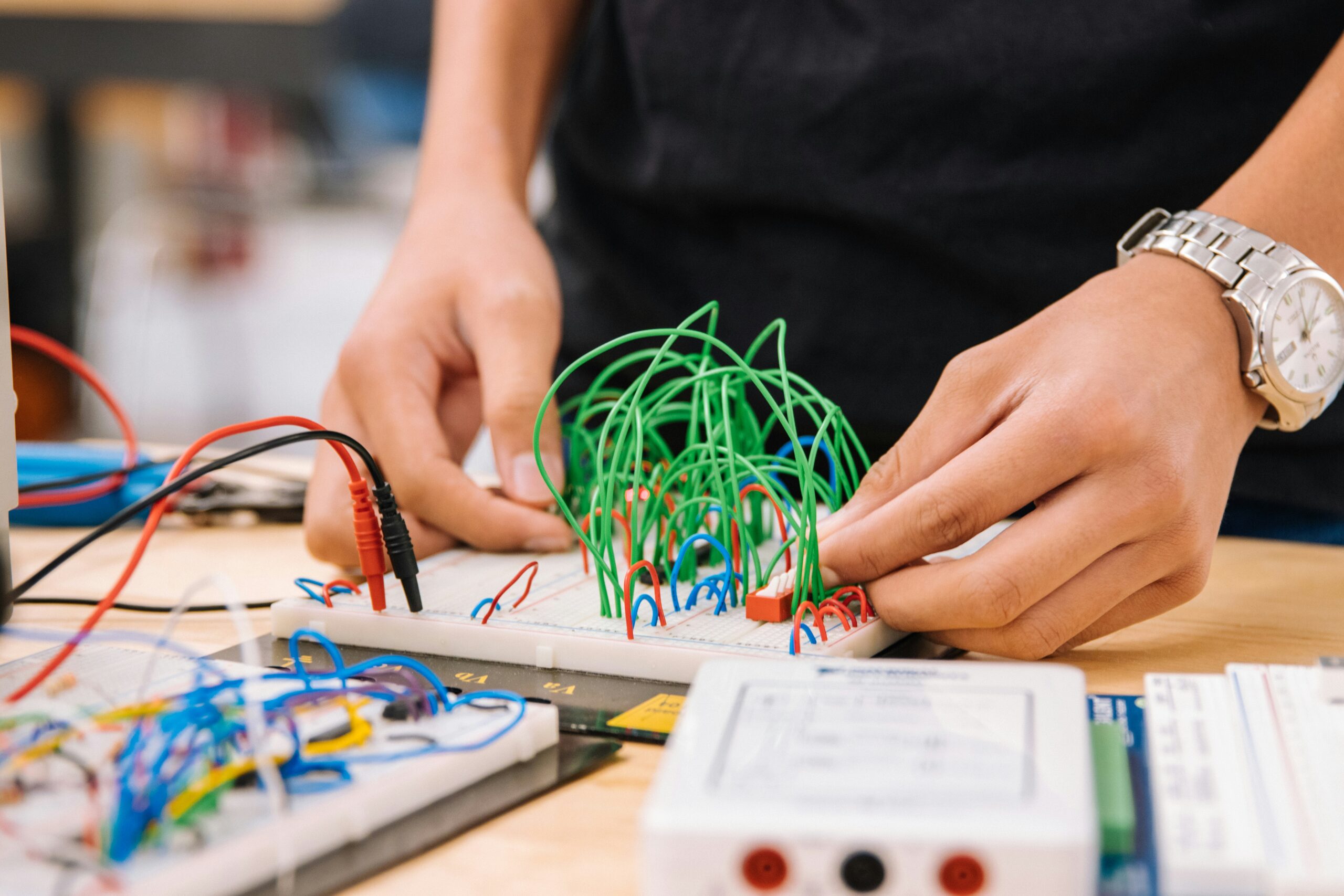

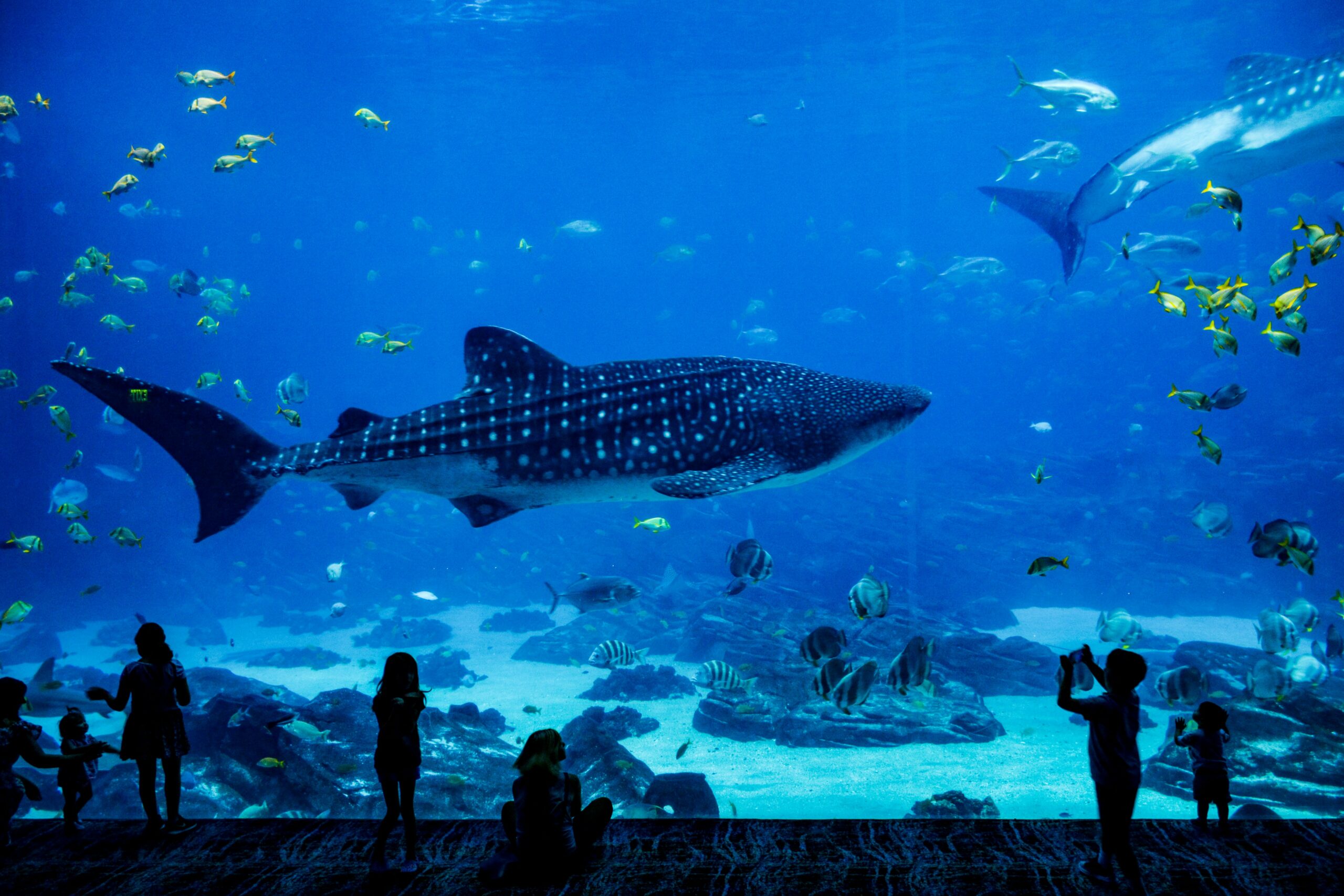

Emergency responders in the exercise were tasked with removing staged victims, including live actors and manikins. A crashed plane and turned-over bus took the stage, and the exact steps of how to treat and administer medical aid to many patients at once were illustrated in real time.

City of Miami Fire Rescue Captain Ignatius Carroll stated, “Every year, we’re always drilling on how to be able to serve better, how to be able to response better, and this is one of these drills where we’re going to really measure our capabilities with not only just the vehicles, but also, we’re looking at the Metrorail trains, then also how it affects day-to-day operations of a hospital area… We have a transition of new people that come in. You have new firefighters, new police officers, new hospital staff, people that come in. Some people have never actually experienced drills of this capacity, so this also gives them an opportunity to basically measure their capabilities, and then also work on those areas.”

According to the organizers, this is the first event of many. Varying scenarios are in their purview in order to adequately test a comprehensive array of skills. Once the event is over, Torres says, “After this, we now do surveys, we do briefings… We collect all the data points, and we do what’s call an after-action report. With the after-action report, we identify areas of improvement, what went well, what could have gone better, and we implement those changes and those improvements.”