Image credit: Unsplash

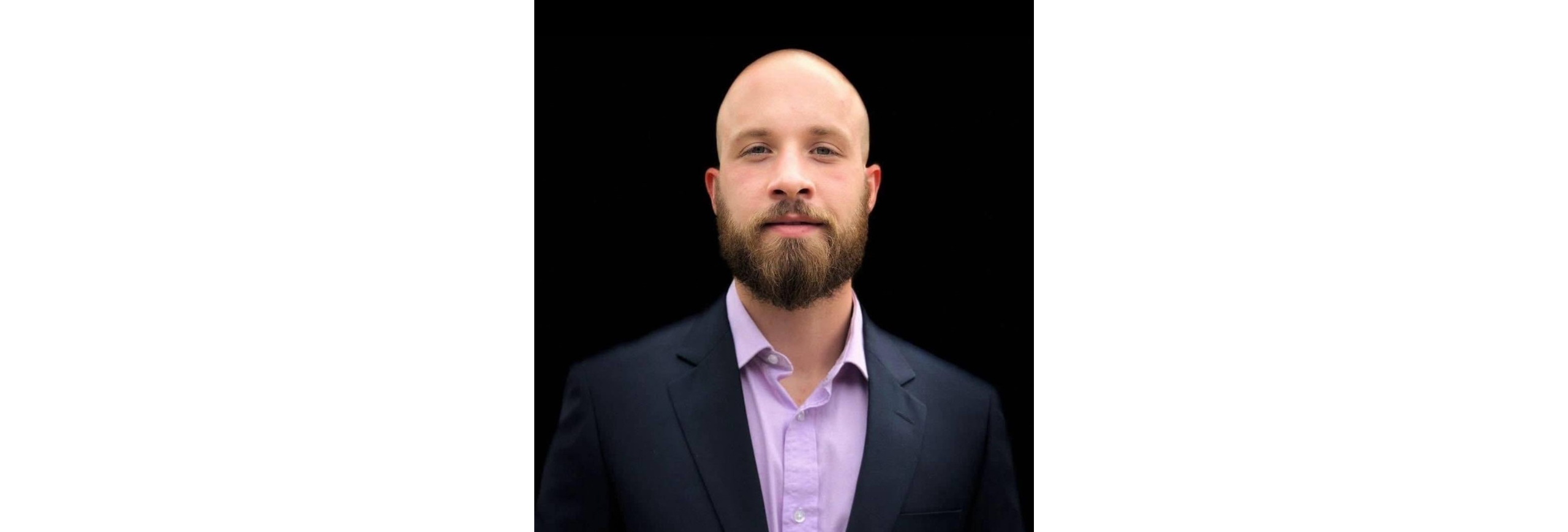

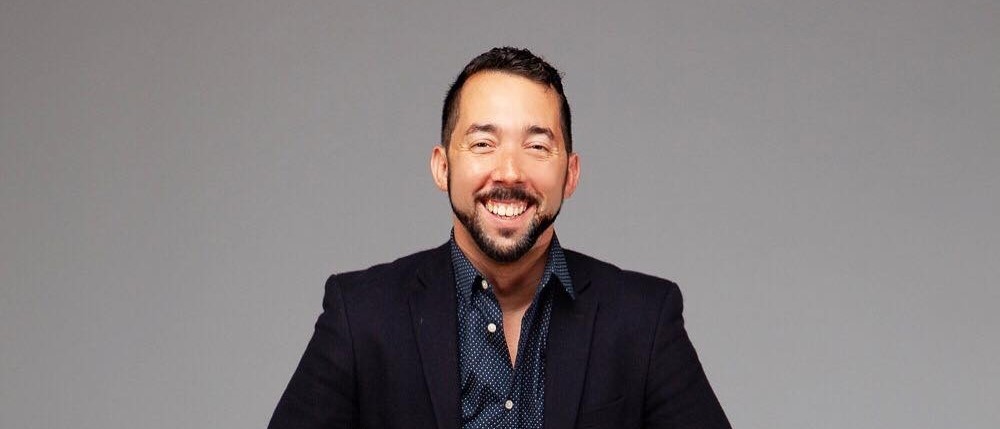

For over two decades, a small group of black military veterans has been gathering in a North Miami-Dade McDonald’s for breakfast each morning — other than Christmas Day.

The group, which is sometimes not-so-small — reaching almost 20 people on a good day — gathers at table 112 beginning at about 9:00 a.m. Of course, they often mingle well past breakfast hours. On one recent weekday morning, an elderly woman in a wheelchair approached a touchscreen kiosk behind the group, unaware that breakfast hours were over. The woman turned to marine veteran Roosevelt Randolph and said, “There ain’t no biscuits?”

“Hell nah, they don’t got no biscuits!” spoke Randolph, 77. The entire dining area erupted with hilarity.

The group has affectionately become the undisputed VIP’s of the McDonald’s located at 9250 NW 7th Ave. due to their long-standing unofficial reservation. Often lingering for hours, the group swaps stories, cracks jokes with each other, and often unintentionally draws an audience. Despite being a regular congregation every morning, sat around trays of sausage biscuits and hash Browns for 20 years, the group has never adorned an official title.

In 2012, Brian Bentancourt became co-owner of the franchise. He has since estimated the group spends approximately $18,250 each year at the location. However, he believes their patronage far surpasses the dollars spent.

Bentancourt said, “They take care of this restaurant like it’s their own.” He continued, “A fun, nice vibe in a restaurant is extremely key. There is an extremely warm vibe when you walk in [because of them].”

For the men of table 112, joining the military was not exactly an option but the only choice that many of them ever had.

“A lot of us couldn’t afford to go to college,” says Randolph. “So the military was the next best thing for us to do.”

Randolph grew up in a single-parent household as a young boy on welfare in the 1960s, which for him, culminated in a resentment for civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Randolph recalls being forced to ride in the back of the bus in Miami and did not understand how social justice could improve his circumstances.

“I hated him because I didn’t like the fact that black people were getting beaten up [in downtown Miami] and getting dogs put on them [and sprayed] with a water hose.” Randolph added, “I didn’t have anybody in my family to tell me what that was all about.”

Randolph ultimately returned to Miami in 1969 after completing two tours in Vietnam, bringing an entirely different frame of mind with him. Now, he understood King’s mission. Of course, he recalls seeing friends and going out when he got home but the horrors of war weighed on him.

“Everybody coped with a lot of stuff when I got back from Vietnam,” Randolph said. “Guys were snorting coke, smoking weed, and some other things.”

The men of table 112 range in age from 62 to 90, with the likes of one Leonard Hopkins as their elder statesman. A man whose presence has become even more notable since he retired from his work as a mechanic in 2016.

Hopkins grew up in Coconut Grove in the 1940s, spending most of his time at his grandfather’s bicycle shop. Fascinated by mechanics of all kinds, he initially planned to study aviation after high school but was hit with an unfortunate dose of reality in 1951 America.

Hopkins recalls, “Three of us went down to Lindsey Hopkins [Technical College], and they told us Blacks couldn’t take aviation.” He continues, “All three of us went and joined the Air Force.”

While racism kept him from pursuing his childhood dreams it did not hold Hopkins back from joining the Air Force where he served eight years as a gunner on a B36 plane, and still beams with pride when discussing that plane and all of its intricacies.

“What I didn’t know was that about 80% to 90% of the black people in the Air Force were in food service or in the motor pool,” Hopkins said after finding out he was among a small number of black airmen to work on a plane.

The youngest member of the group is 62-year-old Jeffrey Berry, a Navy veteran who has driven a charter bus for the last 36 years. Berry recalls leaving Miami in 1980, just before the McDuffie riots broke out.

Before Being a member of table 112, he would get coffee before work at the McDonald’s and was intrigued by the group’s consistency. He introduced himself about six or seven years ago and quickly became friends. Berry found camaraderie with the group as being part of those who have served in the country’s armed forces.

“I think a lot of these kids need to go into the military to learn some structure and some discipline,” Berry said. This life “ain’t no individual thing,” he continued. “No, it takes all of us to do this.”

The group remains just as bonded today as ever with some carpooling to the restaurant each day. Many belong to a group text together, and Randolph and Berry recall even attending the funerals of former members.

Miami continues to change around the controlled environment of the local McDonald’s. Many black residents have been forced to move due to gentrification, and the costs of homes have skyrocketed.

“I said if I ever get in a position to buy it back, I’d like to buy it back,” Hopkins spoke on his childhood home. “I just wanted to have that house in my family because that was the house I was born in.”

Hopkins’ childhood home in Coconut Grove was constructed in 1931 by his father, shortly before he was born. However, his family no longer owns it, and the cost of the home is estimated to be between $3 and $5 million.

As Hopkins left the group recently one morning, two others were just arriving to sit down. The next day, and the next day, and so on, the group continues to return to table 112, though they never stop to question why or define their motives. It is simply their bond and the memories they’re building together that keep them coming back.